The 1905 Scandal that outlawed Tontines

The 1905 scandal that led to the outlawing of a revolutionary investment product

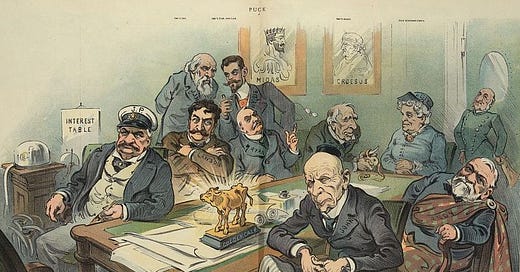

The Gilded Age was a time of great prosperity and excess, a time when the wealthy and powerful lived in opulence while the rest of the country struggled to make ends meet. But beneath the shiny veneer of this glittering Age, there was a dark underbelly, a world of corruption and fraud.

One of the most shocking scandals of the Gilded Age was the Wall Street Scandal of 1905, a scandal that rocked the financial world and exposed the corruption and greed that had taken hold of the nation's largest financial institutions. At the centre of this scandal was the Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States, one of the country's largest and most powerful insurance companies.

The Equitable was founded by Henry Hyde, a visionary businessman who had revolutionized the insurance industry with his introduction of the tontine policy. The tontine was a type of life insurance policy that combined elements of life insurance with an investment scheme. Policyholders paid a monthly subscription fee for five, ten, fifteen or twenty years. If the policyholder died before the end of the term, their beneficiaries received a death benefit, but any accumulated dividends were forfeited. If a policyholder missed a single monthly payment, they received no death benefit, dividends or nonforfeiture value.

Hyde's tontine policies were a huge success, and by 1905, two-thirds of all life insurance in force was of this type. But behind the scenes, the Equitable was a cesspool of corruption and fraud. The company's executives, including Hyde's own son, James Hazen Hyde, were lining their pockets with the money that was supposed to be going to policyholders.

The scandal came to a head in January 1905 when James Hazen Hyde threw an extravagant costume ball at Sherry's, a popular New York City restaurant. The party, which was themed after the Palace of Versailles, cost $200,000 (over $6.7m in todays money) and was charged to the company's account. The party was widely covered in the press, and the public was outraged at the extravagance of the event, especially at a time when many policyholders were struggling to make ends meet.

The public outrage led to an investigation by New York State, which was headed by Charles Evans Hughes. Hughes's investigation of the insurance industry was a relentless pursuit of the truth. The powerful interests in the industry fought back, seeking to remove Hughes from the investigation by nominating him as the party's candidate for Mayor of New York City, but Hughes refused the nomination, determined to see the investigation through to the end.

He uncovered a web of corruption that reached the highest levels of the financial industry, exposing payments made to journalists, lobbyists, and legislators, as well as conflicts of interest and exorbitant executive compensation at a time when policyholders were being shortchanged.

His efforts ultimately led to the resignation or firing of most of the top-ranking officials in the three major life insurance companies in the United States, and he convinced the state legislature to bar insurance companies from owning corporate stock, underwriting securities, or engaging in other banking practices, in order to prevent such conflicts of interest and corruption in the future.

While the investigation and subsequent regulations were able to curb this corruption and fraud, it also had the unfortunate side effect of banning tontine policies.

But in hindsight, it's clear that the problem wasn't with the tontine concept itself but rather with the lack of oversight and corrupt practices that allowed a company like the Equitable to abuse the system.

Tontines were popular because they made sense for people looking to share the risk of longevity - the risk of living a long time. But in the 118 years since the scandal, this type of risk sharing has been limited to defined pension plans or annuities issued by insurance companies.

However, with the advent of modern technology like cloud computing and advanced actuarial algorithms, it's now possible to create a completely fair and transparent tontine. Given this, it's worth considering bringing tontines back with the right oversight and regulations in place. With tontines, individuals would have another option to share longevity risk and potentially improve their retirement outcomes.

It's time to take a fresh look at the tontine concept and not let the corruption of the past prevent us from exploring its potential benefits.

This longer article from the Oxford Centre for Global History is worth a read.